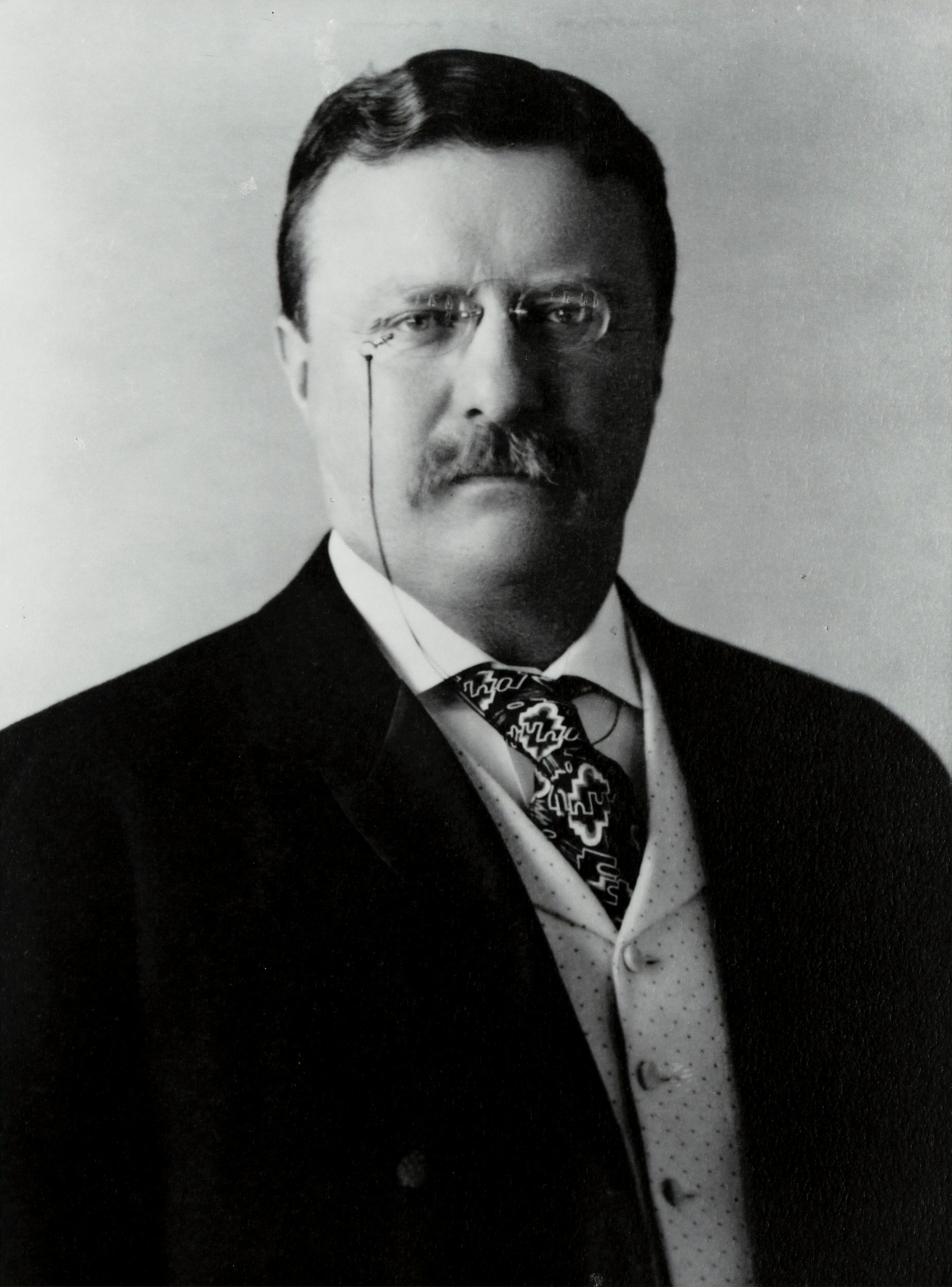

Theodore Roosevelt | The Strenuous Life

"Death had to take Roosevelt sleeping, for if he had been awake, there would have been a fight."

Vice President Thomas Marshall, January 7, 1919

The boy sat on the edge of the leather bench in the second-floor gymnasium, wheezing slightly from his climb up the stairs. Sweat dampened his collar despite the cool October air drifting through the windows. His father stands in front of him, his imposing frame silhouetted against the afternoon light, surrounded by the parallel bars, weights, and rings he'd just had installed.

"Son," his father said, his voice firm but not unkind, "you have the mind but you have not the body, and without the help of the body the mind cannot go as far as it should. You must make your body. It's hard drudgery to make one's body, but I know you will do it." The 11-year-old looked up at his father through wire-rimmed spectacles, his chest still rising and falling with effort. The gymnasium equipment loomed around him, but in his father's eyes he saw something. Not pity, but absolute confidence. His father believed he could overcome what every doctor said was incurable.

The boy nodded once, sharply. "I'll make my body," he said, his voice thin but determined. "I'll do it." He had no idea, in that moment, that he was speaking the words that would define his entire life, that the struggle against his own weakness would teach him everything he needed to know about struggle itself.

The Making of Body and Character

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. was born on October 27, 1858 to a wealthy family in New York City. A sickly baby and child who suffered from debilitating Ashma, Theodore was taken to every doctor that could possibly help him. During Ashma attacks, his father, Theodore Sr., would bundle him into a carriage and race through the streets at night, hoping the rushing air might ease his breathing. The attacks were terrifying. While carriage rides and other therapies helped, Doctors in the 1860s could do very little to affect the problem. Their orders were specific to bed rest and the avoidance of exertion.

His father, however, refused to accept his son's fate. On a chilly night in September 1870, an 11-year old Teddy stood in front of his father. They were sitting in the gymnasium he built on the second floor of their home, and he leveled with his son, stating that all the money and all the doctors could do nothing to help him. "Theodore,” he continued, “you have the mind but you have not the body, and without the help of the body the mind cannot go as far as it should. You must make your body." Teddy’s younger sister, was also in the gym, later wrote that her brother was immediately resolute, that he smiled, and declared, “I will do it!”.

From that day onward, Teddy began a tough regimen of weightlifting, boxing, and wrestling that would continue for the rest of his life. Progress came slowly, his diary records repeated failures and frustrations, but he persisted. He still had the ashma attacks, and he still got sick, but as he challenged his body and pushed it, it got stronger. His lungs got stronger. His health became better. By his late teens, the attacks had diminished almost entirely. He'd learned something profound: through work and grit, the body could be disciplined, strengthened, and bent to the will.

Education for the young Roosvelt was a form of homeschooling. He and his sisters were individually taught and their studies curated. This continued until Roosevelts college years, where he attended Harvard. At Harvard, Roosevelt threw himself into everything with manic intensity. He studied natural history, boxed (despite terrible eyesight that left him nearly blind in one eye after a particularly brutal match), and courted Alice Hathaway Lee. It was during this time that he began to fashion his moral philosophy. This came from unlikely sources. Part Christianity inherited from his father's charitable work among New York's poor, part social Darwinism absorbed from his natural history studies, and part civic republicanism drawn from his voracious reading of ancient historians.

His father's sudden death in 1878, during Theodore's sophomore year, formed everything into a single conviction: that privilege demanded action, not leisure. Theodore Sr. had been enormously wealthy but had spent his evenings working at the Newsboys' Lodging House and championing reforms for the city's orphans and disabled. His son never forgot that. Roosevelt came to believe that educated, wealthy men who retreated into private comfort were committing a kind of moral treason against the republic. He rejected the idea of his Harvard classmates who viewed politics as business best left to professionals, and he rejected equally the deterministic social Darwinism that excused inaction by claiming the strong would naturally prevail. Instead, Roosevelt synthesized something distinctly his own: the belief that physical, moral, and intellectual strength was meaningless unless deployed in service of justice and the common good. It was a philosophy that would make him insufferable to many of his contemporaries but would also make him one of the most consequential presidents in American history. He would spend his life trying to live up to his father's example, and in the process, he would lead an entire nation toward a more active, more engaged vision of citizenship.

The Lights Go Out

Roosvelt and Lee married in 1880, and he immediately entered New York politics as a Republican assemblyman. He was twenty-three years old, impossibly energetic, and challenge to his colleagues who found his moral certainty grating. Life was moving as he thought it should. All of that changed on February 14, 1884. Early in the morning, Roosevelt received a telegram at the state capitol in Albany: come home immediately. He took the first train to Manhattan where he learned that his mother had died and his wife was very ill, both in the same house, on the same day. His mother, Mittie, had succumbed to typhoid fever. Alice was gravely ill, and as he held her in his arms bringing her comfort, she passed away from kidney failure. There is little written about this specific moment outside of what Roosvelt himself shared. He would never speak Alice’s name again, not even in his biography. In his diary, Roosevelt drew a large X across the page and wrote, "The light has gone out of my life."

Drowning in grief, he fled west to the Dakota Territory, to a ranch he'd purchased on a whim the year before. There, in the Badlands, Roosevelt became a cowboy. He drove cattle, hunted grizzly bears, and wrote about the natural world with the eye of a trained naturalist. His ranch hands initially mocked the bespectacled easterner, but his willingness to work as hard as any of them, and his absolute fearlessness in pursuing horse thieves across the frozen prairie, won their respect. He famously said that "black care rarely sits behind a rider whose pace is fast enough," and for three years he certainly rode fast. When he returned to New York in 1886, he was twenty pounds heavier, hardened by the West, and ready to engage with life again. The grieving man had become a force of nature.

"The Crowded Hour"

Roosevelt's return from the Dakota Territory in 1886 marked the beginning of a political career. He lost his first campaign for mayor of New York City but refused to disappear into obscurity. Instead, he accepted an appointment to the U.S. Civil Service Commission, where he made enemies by actually enforcing merit-based hiring. As New York City's Police Commissioner in the mid-1890s, he prowled the streets at midnight to catch officers sleeping on duty or taking bribes.

Eventually, he became Assistant Secretary of the Navy under President McKinley. There, he spent his days modernizing the fleet and his evenings reading naval strategy. When his boss, Secretary John Long, took an afternoon off on February 25, 1898, Roosevelt cabled Commodore George Dewey in Hong Kong with orders to prepare for operations against the Spanish fleet in the Philippines should war come. Long returned the next day, horrified at his subordinate's audacity, but the orders stood. When the USS Maine exploded in Havana harbor days later, killing 266 American sailors, the nation's march toward war became inevitable. Roosevelt had positioned the Navy correctly.

But watching others fight from behind a desk in Washington was unbearable to him. Despite the protests of his second wife Edith, who'd given birth to their youngest son just three months earlier, Roosevelt resigned his Navy post to organize a volunteer cavalry regiment. The newspapers immediately dubbed them "Roosevelt's Rough Riders," and the name stuck. Roosevelt served as lieutenant colonel under his friend Colonel Leonard Wood, and together they assembled one of the most unique military units in American history. Cowboys from the Dakota Territory rode alongside Ivy League athletes from Harvard and Yale. Gamblers, lawmen, Native American scouts, and the occasional outlaw filled the ranks. Roosevelt handpicked many of them himself, seeking men who could ride and shoot, qualities that would prove essential in the Cuban campaign ahead.

Training camp in San Antonio was chaos. The men learned to drill in the Texas heat while Roosevelt drilled them in his philosophy of warfare: aggressive action, moral courage, and absolute fearlessness in the face of the enemy. He bought his own Brooks Brothers uniform (in blue, since the Army had run out of khaki), armed himself with a pistol salvaged from the USS Maine, and prepared to test himself in combat. The regiment shipped out to Cuba in June 1898, though bureaucratic incompetence meant they had to leave most of their horses behind.

The jungle hills outside Santiago provided Roosevelt with what he would later call his "crowded hour", the moment when everything he'd preached about the strenuous life would be tested under fire. On July 1st, the Rough Riders found themselves pinned down by Spanish soldiers firing from entrenched positions on Kettle Hill. Artillery shells burst overhead. Men fell around Roosevelt, who remained on horseback (one of the few mounts that had made it to Cuba), making himself an obvious target. When the order finally came to advance, Roosevelt spurred his horse Little Texas forward, shouting for his men to follow. They surged up the hill through grass and barbed wire, Roosevelt far in front, bullets snapping past his head. He later admitted the charge was "great fun," a phrase that horrified those who saw how many men died that day.

The fight for Kettle Hill merged into the assault on San Juan Heights, and by day's end, Roosevelt and his Rough Riders held the high ground overlooking Santiago. War correspondent Richard Harding Davis wrote that Roosevelt was "the most magnificent soldier I have ever seen." The Spanish garrison surrendered two weeks later, and when Roosevelt returned to New York in August, he found himself the most famous man in America. The crowded hour had transformed him from a politician playing at soldier into a genuine war hero, and it paved the road straight to the governor's mansion.

"Speak Softly and Carry a Big Stick"

As governor, Roosevelt proved impossible to control. He pushed through civil service reform, fought corporate monopolies, and ignored the wishes of Republican Party boss Thomas Platt, who'd expected a grateful and compliant executive. Platt decided Roosevelt needed to be neutralized, and the vice presidency seemed like the perfect political grave, dignified enough to satisfy Roosevelt's ambition but powerless enough to keep him from causing further trouble.

The plan backfired spectacularly.

On September 6, 1901, while Roosevelt was hiking in the Adirondacks, an anarchist shot President McKinley. Roosevelt rushed to Buffalo, but McKinley seemed to be recovering, so he returned to his mountain vacation. Then, on September 13th, a messenger found him on Mount Marcy with urgent news: the president was dying. Roosevelt descended the mountain in darkness, was driven forty miles by wagon over terrible roads, and caught a special train to Buffalo. He arrived too late. William McKinley died in the early morning hours of September 14th, and Theodore Roosevelt, at forty-two years and ten months, became the youngest president in American history. Boss Platt reportedly groaned, "Now look, that damned cowboy is President of the United States!"

The cowboy wasted no time proving Platt’s concerns. Roosevelt took on the titans of industry, filing forty-four antitrust suits and breaking up monopolies that had seemed untouchable. He settled the coal strike of 1902 by threatening to seize the mines, the first time a president had intervened in a labor dispute on behalf of workers rather than owners. He also championed the Pure Food and Drug Act and the Meat Inspection Act after reading Upton Sinclair's "The Jungle,. These regulations that saved countless lives.

His foreign policy followed the same principle he'd articulated: "Speak softly and carry a big stick; you will go far." He sent the Great White Fleet around the world to demonstrate American naval power. He mediated the end of the Russo-Japanese War, earning the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts. When Colombia refused to allow the United States to build a canal across Panama, Roosevelt – whether fortunately or unfortunately – supported/engineered a Panamanian revolution, recognized the new nation within hours, and secured the rights to build his canal. Critics howled that he'd violated international law. Roosevelt couldn’t have cared less. He wanted the canal built, and he wanted it built immediately. He said, "I took the Canal Zone and let Congress debate; and while the debate goes on, the canal does also."

Domestically, Roosevelt's conservation legacy may have be his greatest achievement. He understood, in a way few Americans did in 1900, that the nation's natural resources were not infinite. With this understanding, he established the United States Forest Service, created fifty-one federal bird sanctuaries, four national game preserves, five national parks, and eighteen national monuments including the Grand Canyon. He protected approximately 230 million acres of public land. When Congress tried to stop him through a bill that removed his authority to create new forest reserves, Roosevelt worked around the clock with his chief forester to designate twenty-one new forests before signing the bill into law. It was classic Roosevelt, technically legal, probably justified, and absolutely audacious.

The Bull Moose

Theodore Roosevelt left office in 1909, handing the presidency to his chosen successor, William Howard Taft. He was only fifty years old, still bursting with energy and ideas, and convinced he'd return to politics when the time was right. That time came in 1912. Frustrated with Taft's conservatism and convinced the Republican Party had betrayed progressive principles, Roosevelt challenged his former friend for the nomination. When the party bosses chose Taft at the convention, Roosevelt formed the Progressive Party, better known as the Bull Moose Party after he declared himself "as strong as a bull moose."

The 1912 campaign was vicious. Then, on October 14, a saloonkeeper shot Roosevelt in the chest before he was scheduled to give a speech in Milwaukee. The bullet struck his eyeglass case and the folded fifty-page speech in his coat pocket, slowing it enough that it lodged in his chest muscle instead of penetrating his lung. Roosevelt felt the wound, coughed into his hand to check for blood in his lungs, found none, and proceeded to deliver his ninety-minute speech. "Friends," he began, "I shall ask you to be as quiet as possible. I don't know whether you fully understand that I have just been shot; but it takes more than that to kill a Bull Moose."

Roosevelt lost the 1912 election to Woodrow Wilson, but he'd accomplished something remarkable, he'd split the Republican vote and proven that a third-party candidacy could be viable in American politics. More importantly, he'd forced both major parties to embrace progressive reforms they might have otherwise ignored. His platform had called for women's suffrage, an eight-hour workday, workers' compensation, and social insurance programs that wouldn't be enacted until Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal twenty years later.

In his final years, Roosevelt yearned to lead American troops in World War I, but President Wilson denied his request. His youngest son Quentin was killed in aerial combat over France in 1918, and Roosevelt never recovered from the loss. When he died in his sleep at Sagamore Hill on January 6, 1919, the nation mourned the passing of a man who'd seemed too energetic, too vital, to ever die. Vice President Marshall's quipped, "Death had to take Roosevelt sleeping, for if he had been awake, there would have been a fight."

The Strenuous Life

If you ask most Americans what they know about Theodore Roosevelt, you're likely to get all kinds of answers. "He was a Rough Rider," "He liked to hunt," or "He's the guy on Mount Rushmore", or much worse.

The reality is far more complex and, frankly, more interesting. He was sickly as a child and devastated by personal tragedy. He could be vain, impulsive, and utterly exhausting to those around him. His views on race and empire were products of his time and make many uncomfortable today. But Theodore Roosevelt left an indelible mark on American life that extends far beyond his seven years in office, and his philosophy of living what he called "the strenuous life" speaks powerfully today just as it did in 1899.

What often gets lost in the mythology of Roosevelt the cowboy and Roosevelt the warrior is Roosevelt the intellectual. He wrote more than thirty-five books on subjects ranging from naval history to ornithology to frontier life. He read voraciously, a book every day throughout his adult life, often more, and could quote Shakespeare, Dante, and the ancient historians from memory. During his presidency, he regularly invited scientists, writers, and artists to the White House for dinner and conversation that would stretch late into the night. He helped found the American Historical Association and was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters. This wasn't a politician affecting intellectualism, this was genuine curiosity about everything from bird migration patterns to medieval poetry. Roosevelt believed that the mind, like the body, had to be exercised constantly, and he approached learning with the same intensity he brought to everything else in his life.

Roosevelt embodied his philosophy. The asthmatic boy who made his body. The grieving widower who rebuilt himself in the Dakota Badlands. The politician who charged up San Juan Hill. The president who took on monopolies, protected wilderness, and built a canal because he believed great nations did great things. He packed several lifetimes into his sixty years, and he did it by refusing to accept limitations, whether imposed by his lungs, his grief, his political enemies, or conventional wisdom about what was possible.

In an age when we're often told to be cautious, to avoid risk, and embrace comfort and self-care, Roosevelt reminds us that the strenuous life, the life of action, purpose, and daring, is where “self-care” finds its ultimate form. Though like all of us, imperfect, he was someone who believed that privilege demanded action, that strength meant nothing without testing and service, and that the worst thing you could do with your one wild and precious life was waste it in comfortable mediocrity.

Folks, I could keep going, but alas, we find ourselves out of time. There are so many more things I would like to share, and hope Jon will ask me about them next week. To close out our time together here, Ill leave you with an excerpt from a speech Roosevelt gave in Chicago, where he challenged his fellow Americans to embrace the strenuous life philosophy: "Far better it is to dare mighty things, to win glorious triumphs, even though checkered by failure, than to take rank with those poor spirits who neither enjoy much nor suffer much, because they live in the gray twilight that knows neither victory nor defeat."